- Home

- Penelope Lively

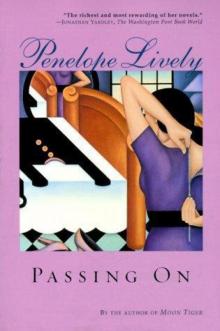

*****Passing On*****

*****Passing On***** Read online

PASSING ON

PENELOPE LIVELY

‘Eternal life is an appalling idea, especially in mother’s case’

Helen is fifty-two and Edward forty-nine when Dorothy, their mother, dies, ending her reign of terror and leaving them ill equipped to deal with their lives. Timid, cautious and naive, Helen makes the charming Giles Carnaby. family solicitor, the object of a belated schoolgirl crush, while Edward, free to express his sexuality at last, finds it gets the better of him.

Dorothy may be dead and buried, but her iron grip continues to hold them in its power.

‘Passing On is about the essential difficulty of being English, of coping with peculiarly English varieties of guilt, nostalgia, frustration and desire’ Jonathan Keates, Observer

‘Lively is at her sharpest, alert to every conceivable irony’

Jonathan Coe. Guardian

‘Lively brilliantly captures the ecstasy and agony of falling in love … A highly plausible, utterly authentic, beautifully written slice of contemporary life’ Val Hennessy, Daily Mail “A story as poignant as it is humorous’

David Hughes, Mud on Sunday

PENGUIN BOOKS

PASSING ON

‘The quiet achievement of Passing On is that it finds drama in the lives of characters so emotionally suffocated that a less penetrating novelist might not have considered them worth writing about’ - Jonathan Coe in the Guardian

‘Edward and Helen in Passing On are pleasant, plain, inarticulate and so insecure that sometimes they become almost invisible … We weep for him, tortured by his homosexuality and loneliness, and for Helen with her once-worn ball-dress, thirty years old, lying shrivelled on her knee. We also want to kick them both. But it would be a small kick … Passing On is Penelope Lively at her best, desolating us one moment by the pain of unloved people, maddening us the next by their feebleness’ - Jane Gardam in the Evening Standard ‘Well written, and often drily, darkly funny’ - Carole Angier in New Statesman & Society

‘This quiet novel will delight Penelope Lively’s devoted readers, of whom the present writer is one … If, as I suppose, novel writing is a strange, delusive and obsessive calling, Penelope Lively makes it seem almost normal, as natural as breathing or going for a walk … Passing On is, for my money, her most attractive novel to date’

- Anita Brookner in the Spectator

‘Treat it like a bar of chocolate or an unjustifiable cream bun and hide it until you have finished it … It is a sensitive and profound tale … Finely caught here is the conflict of the English village of the 1980s … No curate’s egg about Penelope Lively; she is good in every part. Dialogue, description, detail, emotions, pace - she seems to get it all right’ - Rosemary Stoyle in the Literary Review

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Penelope Lively grew up in Egypt but settled in England after the war and took a degree in history at St Anne’s College, Oxford. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and a member of PEN and the Society of Authors. She was married to the late Professor Jack Lively, has a daughter, a son and four grandchildren, and lives in Oxfordshire and London.

Penelope Lively is the author of many prize-winning novels and short story collections for both adults and children. She has twice been shortlisted for the Booker Prize; once in 1977 for her first novel, The Road to Lichfield, and again in 1984 for According to Mark. She later won the 1987 Booker Prize for her highly acclaimed novel Moon Tiger. Her novels include Passing On, shortlisted for the 1989 Sunday Express Book of the Year Award, City of the Mind, Cleopatra’s Sister and Heat Wave. Many of her books, including Going Back, which first appeared as a children’s book, Oleander, Jacaranda, an autobiographical memoir of her childhood days in Egypt, and her recent collection of short stories, Beyond the Blue Mountains, are published in Penguin. Her most recent novel, Spiderweb, is published by Viking and forthcoming in Penguin,

Penelope Lively has also written radio and television scripts and has acted as presenter for a BBC Radio 4 programme on children’s literature.

She is a popular writer for children and has won both the Carnegie Medal and the Whitbread Award.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Private Bag 102902, NSMC, Auckland, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England First published by Andre Deutsch 1989

Published in Penguin Books 1990

13 15 17 19 20 18 16 14

Copyright Š Penelope Lively, 1989

All rights reserved

Printed in England by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding Of cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ONE

The coffin stuck fast at the angle of the garden path and the gateway out into the road. The undertaker’s men shunted to and fro, their hats knocked askew by low branches, their topcoats showered with raindrops from the hedge. The mourners halted around the front door and waited in silence. Birds sang effusively.

At last the men managed to pivot the coffin on the gatepost and proceeded to the waiting hearse. The coffin was loaded. The mourners straggled out into the road and hesitated, unwilling to commit themselves to the attendant limousines.

Louise said, ‘It’s daft using cars to go such a short distance. At least we could have squashed into one, surely?’

There were two Daimlers. Helen and Edward got into the first, the four Dysons into the second. First time I’ve ever ridden in one of these, thought Helen. The last too, let’s hope. They moved off at walking pace, past the Britches, radiant still with birdsong, past the builders’ yard where Ron Paget, heaving planks of timber from the pick-up, suspended the operation and stood in respect, his eyes lowered. Helen nudged Edward: ‘The old rogue — look at him.’ Edward nodded. He said, ‘At least he’s not coming to the church — I wouldn’t have put it past him.’

Now they were passing the shop, where the Birds Eye van driver continued to lift out cartons without looking up. From within, faces watched furtively. Two women with prams paused, tucking themselves into the wall as the cortege went by. A small child pointed, questioning. They are having to explain, Helen thought.

About deaths, funerals. Probably they will dodge the issue with distractions — an iced lollie, a sweetie. All the same, mother has disrupted the lives of others, just a little, for the last time.

Now they were at the church, unloading. The coffin, the flowers, the mourners. Through the lych gate, along the path, a halt at the door to make adjustments before entering. Two of the undertaker’s men were young, Helen noticed; what a very curious choice of occupation. Earlier, she had looked out of the window at Greystones and seen one of them filling in a football coupon while they waited in the hearse. Now, their faces were composed into expressions of noncommittal sobriety.

‘You three should go in first,’ said Tim Dyson. ‘I’ll follow with the children.’

Only two of the family wore black. Tim’s suit was a dark pinstripe but Edward’s was green, shiny around the seat and elbows, brought out for school speech days and probably twenty years old. Helen had put on her camel coat; the late May morning was quite cold and she felt the coat to

be more subdued than her maroon suit, the only other garment suitable for a formal occasion. Louise was in a hotchpotch of unashamed colour and pattern. The two adolescents, alone, were appropriately funereal, clad from head to toe in black leather.

There were twenty or thirty people in the church. The front pew had been left empty. The family shuffled into it. Helen, between her brother and sister, observed the coffin, which had been placed in the aisle just below the steps to the chancel.

It seemed, now, much too small. Helen thought of her mother’s stocky form, eyed the coffin, and could not imagine her squeezed into it. She gazed at the varnished wood and the brass handles and waited to hear cries of protest and complaint. She half expected to have to rise to her feet and set things right.

Glancing at Edward, she knew that he was thinking exactly the same.

‘Let us pray . .

Helen sank obediently to her knees. She said, ‘O God, now that she is Thine rather than mine, do something about her. If she was created in Thy Image, then the system is an imperfect one.

‘We consume away in Thy displeasure: and are afraid at Thy wrathful indignation. .

No, not mother. She wasn’t much more of a Christian than I am. A token one, being a natural conservative. But I doubt if she ever gave a thought to Thy displeasure, any more than to anyone else’s.

The service proceeded. The congregation sang a hymn, creakily’.

Louise and the children were silent; Edward and Helen moved their lips; Tim Dyson gave tongue firmly in a light tenor.

Helen allowed herself a glance sideways and backwards to see who was there. Expected faces. Village faces, more distant relatives, Doctor Taylor, someone middle-aged who must be Mr Carnaby from Carnaby and Proctor, solicitors, to whom Helen had spoken on the phone but had not met. Dorothy Glover, at eighty, had not had friends. Indeed she had not had many at sixty or at forty or even, perhaps, at twenty. Helen could think only of someone she did voluntary nursing with during the war, who sent Christmas cards, and a woman who shared her interest in a mystical form of healing involving a black box with a lot of wires and buttons, with whom she corresponded.

Mother was not a nice woman. I have always known that, and I can say it, because I am her daughter and so in the nature of things came nearer to loving her than anyone else ever did. As did Edward. Louise’s attitude is rather different, for various reasons.

Louise, right now, appeared to be suffering. Her face had become contorted; she was reaching for a Kleenex with which she scrubbed both eyes, angrily. As the hymn ground to its end she hissed to Helen, ‘Bloody hay fever! It’s those blasted flowers.

Why did we have to have them?’

‘Because they were sent.’

The flowers were rather awful: gladioli and enormous white daisies that looked artificial, and tightly budded roses fanned out behind windows of cellophane. And a couple of wreaths of shiny, hard-looking leaves. These offerings had ridden in the hearse and were stacked now outside the church door. Helen hoped they would not be brought back to the house: she was vague about what the etiquette was here. She longed to be rid of the flowers, of the appalling hours that loomed in which she must dispense hospitality and talk to people, of the whole disagreeable day. She simply wanted to get on with life, which would now be different.

She wanted, quite dispassionately, to see what this difference would be. She was also extremely tired. Her mother had died indignantly and demandingly. Neither she nor Edward had had much sleep for quite a while.

And out now into the churchyard, trailing behind the coffin.

The hole; the pile of fresh-dug earth. Oh God, thought Helen, this is too awful. Why isn’t she being cremated? She is not being cremated because she specified that it should be like this. All in black and white, it appears. Burial in the churchyard of St Peter’s, Long Sydenham, in a plot in the far corner near the big sycamore that she laid claim to several years ago, apparently — after, it emerges, a row with the rector that none of us knew a thing about. Now I know why he’s been giving us funny looks for so long. So mother envisaged us all here, gathered round staring down in this ghastly way, looking at anything rather than each other, wishing they’d get on and get it over. You could have spared us that, mother.

Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. The words, in fact, are beautiful — the rhythms, the resonance. The meaning is another matter, for us unbelievers. Mercifully. Eternal life is an appalling idea, especially in mother’s case.

And that, at last, was that. They could start to turn away, look at each other, they could leave her there under the sycamore and go. And now, damn and blast it, Helen feels tears prick her eyes, surge up, begin to trickle — and she looks at Edward and sees that he is the same. They both scowl and furtively dab. We can’t leave her here, thinks Helen, we can’t just put her in there and leave her. Mother.

But they can. And do. She is dead. Helen thinks, almost for the first time, mother has died. She is not here any more.

Incredulous, she searches the group around the grave: Edward, Louise, Tim, Suzanne and Phil. No mother, any more.

‘I thought they’d never go,’ said Louise. ‘Cousin Phoebe — may I be preserved from cousin Phoebe, now and for ever. Who was the good-looking bloke with the silver hair?’ She stood at the drawing-room windows, open into the garden, sniffing and mopping her eyes. ‘Oh those bloody flowers. .

‘Surely,’ said Helen, ‘there must be some flowers in Camden?’

‘Not a lot. Anyway florist ones are worse, for some reason.

Was he the solicitor?’

‘Yes. He’s writing to us all. About the Will.’

‘Oh, all that bumph …’ said Louise vaguely. suppose you wouldn’t think of selling the Britches now? Make this place a bit more comfortable? It’s perishing cold, as usual — frankly I don’t know how you endure it.’

‘Of course we’re not going to sell the Britches,’ said Edward.

They stood at the window, the three of them, and looked into the garden, on which rain now fell once more, after a tactful intermission for the funeral. It was defiantly unkempt; the lawn was a hayfield, the yew hedge drooped almost to the ground, the only surviving plants were vigorous shrubs and a few creepers swarming up above the general level of growth. None of them saw this, since it had been ever thus.

Louise saw fuming pollen, and longed for the tarmac of North London. Helen saw their mother, thick-set, irritable, wearing brown corduroy, stumping across the grass with a query or an order on her lips. Edward saw a flycatcher, a pair of great tits and a collared dove. He looked for the flycatcher’s mate, and wondered where the nest was.

They did not look like siblings. Helen and Edward, at fifty two and forty-nine respectively, were not physically alike though they shared a certain style: Edward’s shiny suit, Helen’s rather unbecoming dress, obviously chosen without interest or prolonged thought. Edward was fair, thin, blue-eyed, and slightly stooping; Helen was shorter, brown-haired and fresh-faced, a woman who would be unremarkable in a group — only a second glance would reveal distinctive features: the bright eyes, the neat set of the nose. Louise, ten years younger, seemed of another generation and culture — her clothes raffish but also metropolitan, her hair unruly but tinted with salon highlights.

Of course not,’ said Louise, turning from the window. ‘I never really imagined you would.’ She patted Edward’s arm. ‘You’d feel uncomfortable being comfortable, wouldn’t you? I’ll help you wash up and then we’d better push off. Where are the others?’

‘Taking glasses into the kitchen,’ said Edward. ‘Don’t bother about the washing-up.’

Louise flung herself into a chair. ‘All right. Maybe the kids’ll do it. Wonders never cease.’

Helen picked up a plate of uneaten bits and pieces and took them through to the kitchen, where Tim Dyson stood looking with distaste at the crammed sink. It was a large, low ceramic sink, of the kind more often seen nowadays in a garden, planted with alpines. Quite po

ssibly Tim did not recognise it as a sink, being accustomed to stainless steel. He always avoided the kitchen at Greystones; in fact Helen could not remember having seen him in there before. Normally, he kept to the drawing room and the dining room while domestic chores were being undertaken; he had not spent a night in the house for many years.

Louise, during her mother’s illness, had visited on her own.

The children — it was hard to think of them now as children, given their appearance, but fifteen and sixteen is more child than adult — were eating sausage rolls. Suzanne swallowed quickly and said, ‘I’ll wash, Helen — I don’t mind.’

‘Don’t bother. We’ll do it when you’ve gone. I think Louise wants to be off.’

Suzanne’s metamorphosis was less startling than Phil’s. Her hair stuck up spikily from her scalp in a way that seemed to defy gravity, her eyes were black-rimmed and there was a general impression of leather and metalwork. Phil, though, was almost unrecognisable. Helen’s first reaction had been that someone had followed Louise and Tim into the house, then that Louise had let Phil bring some undesirable friend, that it was too bad of Louise, that he certainly couldn’t be allowed to come to church, and at last, with pure astonishment, that this was Phil. He too was black-leathered and slung about with chains; his boots had spurs; there were chrome studs all over his back. It was his head, though, that startled most: the shaven scalp, the jet-black crest with streaks of emerald. Helen, punch-drunk with strain and exhaustion, had been on the edge of hysterical laughter. Neither Louise nor Tim had apparently thought the matter worth comment. Presumably they were so used to it. Helen had not seen either of the children for almost a year, she realised. A year

is a long time, in more eventful lives. Louise and Tim led eventful lives. All Louise’s phone calls were catalogues of activity and disaster; they were both always over-worked, over-stressed, on the brink of startling achievement or notoriety, and plagued by minor illness. Louise had hay-fever, cystitis and migraine; Tim had high blood pressure and sinus trouble. They were always in need of holidays for which they could not be spared.

The House in Norham Gardens

The House in Norham Gardens Family Album

Family Album Life in the Garden

Life in the Garden Oleander, Jacaranda: A Childhood Perceived

Oleander, Jacaranda: A Childhood Perceived Cleopatra's Sister

Cleopatra's Sister Next to Nature, Art

Next to Nature, Art A Stitch in Time

A Stitch in Time Moon Tiger

Moon Tiger The Photograph

The Photograph Heat Wave

Heat Wave Pack of Cards

Pack of Cards Spiderweb

Spiderweb How It All Began

How It All Began Treasures of Time

Treasures of Time The Road to Lichfield

The Road to Lichfield Passing On

Passing On Making It Up

Making It Up Judgment Day

Judgment Day The Purple Swamp Hen and Other Stories

The Purple Swamp Hen and Other Stories Consequences

Consequences *****Passing On*****

*****Passing On*****